A few days ago, I spotted a large (about 2 inches, or 5 cm, long), wasp-like insect nectaring on swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) in my garden. Although it looked like a wasp, I suspected that it wasn’t because it appeared to have only one pair of wings and it didn’t have a narrow, wasp-like waist.

Archive for the ‘Nature’ Category

The “Mydas” Touch

Posted in Insects, Native Plants, Nature, tagged Asclepias incarnata, Diptera, mimics, Mydas fly, Mydas tibialis, nectar feeders, swamp milkweed on July 24, 2013| 6 Comments »

Damselfly Hitchhikers

Posted in Ecology, Insects, Nature, Pond life, tagged damselfly, larvae, mites, Odonata, parasite on June 6, 2013| 6 Comments »

A couple of weeks ago, I took a photo of a damselfly that had about two dozen tiny globules stuck to the bottom of its abdomen.

Upon closer inspection, the globules appeared to be bright red with tiny legs, so I suspected they were some type of parasite.

Parasites they were. The tiny red globules were water mites, known scientifically as Hydracarina. There are about 1500 species of water mites in North America, and they’re very common in the shallow areas of lakes, ponds, and wetlands. Some species of water mites are parasites on insects like the damselfly in my photo. Parasitic mite larvae attach to a damselfly larva underwater. When the damselfly larva emerges from the water and enters adulthood, the mite larvae stay with it and also become adults. The mites feed on the body fluids of the damselfly and may get an added bonus of a free ride to a new pond or wetland to colonize. Damselflies and other insects usually survive the mite parasitism but may be weakened by it.

The damselfly in the above photo is a male Fragile Forktail (Ischnura posita), a roughly one inch long damselfly that’s common in eastern North America. Fragile Forktails are distinguished by a pair of broken stripes on the upper thorax that look like exclamation points. In males, the stripes are green. In young females, the stripes are blue. Older females turn a bluish gray overall, and the thorax stripes become less noticeable.

An Elegant Mosquito

Posted in Ecology, Insects, Nature, tagged aquatic, biocontrol, Culicidae, elephant mosquitoes, larvae, mosquitoes, nectar on February 10, 2013| 4 Comments »

… that’s the remark in the bugguide.net species account about this fellow:

This elegant mosquito is actually an Elephant Mosquito (Toxorhynchites rutilus), a species of mosquito native to the eastern US. If the word mosquito conjures up images of swatting at nasty, disease-carrying blood suckers on warm summer evenings, read on, for this is a mosquito of a different ilk.

Gentle giants of the mosquito world

Members of the mosquito genus Toxorhynchites are the largest of the world’s mosquitoes (family Culicidae), with wingspans that can exceed 0.4 inches (12 mm). Unlike most mosquitoes, adult Toxorhynchites don’t take blood meals. Instead, they fill up on protein while they are aquatic larvae—and, lucky for us, they prey upon the larvae of their blood-sucking mosquito relatives. A single Elephant Mosquito larva can down 400 pest mosquito larvae. Elephant Mosquito larvae and their prey are found in water-filled tree holes (they’re also called Treehole Mosquitoes) or human artifacts like tires. Check out this YouTube video by EntoGeek that shows the larvae feeding.

Once they reach adulthood, Elephant Mosquitoes, both males and females, feed only on flower nectar. The male in the above photo was feeding on some goldenrod (Solidago spp) nectar during an afternoon in late summer 2012. You can tell it’s a male from the very feathery antennae that he uses to detect the pheromones of females. The curved appendages on his head are the mouthparts that he uses to feed. Not readily apparent in the photo is the brilliant metallic coloring that Elephant Mosquitoes have.

Effective biocontrol agents

Elephant Mosquitoes have successfully been reared and released to control populations of pest mosquitoes. Although they don’t provide total control, they’re valuable in targeting pest mosquito larvae in tree holes or man-made containers that are difficult to treat with insecticides.

Bumblebee Blues–Another Lobelia and its Pollinators

Posted in Ecology, Nature, Plants, tagged bumblebees, Cardinal Flower, flower color, Great Blue Lobelia, insects, pollination on February 8, 2013| 10 Comments »

My January 12 and 13 posts featured Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis), a plant with bright red flowers that are pollinated by hummingbirds. Another species of Lobelia native to eastern and central North America is Great Blue Lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica—the species name derives from use of the plant roots by Native Americans in a concoction to cure syphilis).

Great Blue Lobelia is similar in outline to Cardinal Flower, but it grows a foot or two shorter and it has blue flowers. Its flowers are similar in shape to those of Cardinal Flower—they’re tubular shaped with two upper and three lower petals—but the flower parts of Great Blue Lobelia are more compact. Both species of Lobelia share the same bloom time and habitat. But they don’t share pollinators, a fact that I observed last summer.

Welcome, Great Blue Lobelia

In summer 2012, I was surprised to discover two plants of Great Blue Lobelia in bloom near the patch of Cardinal Flowers in my backyard. I was surprised because I didn’t plant them. There were some Great Blue Lobelias in the yard until about ten years ago, but they died out, probably due to insufficient moisture. I suspect these new plants may have sprouted from seeds that had laid dormant in the soil. In any case, having these two closely related Lobelia species growing near each other offered a great opportunity to observe the fauna that visited their flowers.

The flower visitors

As described in my earlier posts, the Cardinal Flowers were magnets for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and Spicebush Swallowtail butterflies. But both of these flower visitors totally ignored the nearby Great Blue Lobelia flowers.

On the other hand, the Great Blue Lobelias were abuzz with busy pollination by bumblebees that totally ignored the nearby Cardinal Flowers. Bumblebees were the only insects that I saw visiting the Great Blue Lobelia flowers, although I’ve read that other species of bees and wasps also visit the flowers.

But why this segregation of flower visitors? Flower color is key. Hummingbirds have a strong preference for red flowers. Butterflies have more eclectic color preferences that include red. But bees cannot see red. Bees rarely visit red flowers unless the flowers also reflect ultraviolet light that humans can’t see. Bees prefer blue over other colors, and that’s why they’re attracted to Great Blue Lobelias.

Still, it seemed odd that neither hummingbirds nor butterflies even approached the Great Blue Lobelias and that the bumblebees never stumbled upon the Cardinal Flowers. I wasn’t the first person to make this observation though. Thomas Meehan, a naturalist, made similar observations 112 years earlier:

In my garden during the past year, 1900, I had some fifty plants each of Lobelia syphilitica and Lobelia cardinalis in rows side by side. They were so near each other that some of the flower stems of the latter fell over and seemed to be blooming among the plants of the former. It surprised me one day to note that while numerous winged insects visited the blue-flowered species, none cared for the scarlet ones. This excited an interest that led to a continuous observation through the whole flowering period. At no time did I see an insect visitor on the cardinal flower, while every day the blue-flowered species had abundant attention. On one occasion I found a humming-bird, Trochilus colubris, at work on the cardinal flower, and the zest with which numerous flowers were examined by the bird attested to the presence of nectar, a fact which my own test subsequently verified. The bird is not numerous on my ground, and with an abundance of flowers of various kinds over many acres of ground, it may be inferred that it was not a frequent visitor to the cardinal flower. I observed it only on this occasion. It wholly neglected the blue-flowered species, that seemed so attractive to the insects.

Result—few Lobelia hybrids

Plants of related species that bloom at the same time and attract the same pollinators often hybridize, or interbreed and produce intermediate species. The goldenrods (Solidago spp.) that bloom in late summer and autumn are well-known hybridizers. But Cardinal Flowers and Great Blue Lobelias, with their unique pollinators, rarely hybridize in nature. Of course, that doesn’t stop a meddling human from transferring pollen between the species to see what, if any, hybrids result … something I might try next summer.

Hunchback Bee Fly

Posted in Ecology, Insects, Nature, tagged bee flies, Bombyllidae, Diptera, parasite, parasitoid, pollination, Rudbeckia fulgida on January 24, 2013| 3 Comments »

During the warmer months of 2012, I photographed lots of invertebrates like insects and spiders. I didn’t know much about many of them, including their identities. This winter, I’m reviewing the photos to try to identify and learn more about the subjects.

Here’s a photo I took in August of a fuzzy black and yellow winged insect that had a fondness for Black-eyed Susans (Rudbeckia fulgida, also goes by the common name Eastern Coneflower).

After searching through insect field guides including BugGuide.net, I identified it as a Hunchback Bee Fly (Lepidophora lutea). Bee flies (family Bombyliidae) are members of the insect order Diptera, or flies. Members of this order have only one pair of membranous wings, while most other insects have two pairs of wings. The common name, bee fly, comes from the resemblance of many species to bees. Bee fly is also an apt name because the larvae of many species of bee flies are parasites on the larvae of burrowing solitary bees and wasps.

The scary-looking appendage projecting out the front of the Hunchback Bee Fly is actually a harmless proboscis that the insect uses to feed on nectar and pollen from flowers. Bee flies are important pollinators of many flowering plants. The Hunchback Bee Fly favors Black-eyed Susans and other members of the Aster (Asteraceae) plant family that are in bloom in July and August when the adult insects are active.

Bee flies are strong fliers that can hover and quickly dart about in all directions. Bee flies use their hovering skills during mating and while feeding on flowers. Female bee flies also hover near the ground while searching for the entrance of a bee or wasp nest to host their offspring. If the bee fly spots what looks like a nest entrance, she’ll fling an egg toward it from her hovering position with remarkable accuracy.

A Smaller, Furrier Bee Fly

I had already been aware of another species of bee fly that’s common in my area–one that is smaller, more rounded, and furrier-looking than the Hunchback Bee Fly. This other species is called the Greater Bee Fly (Bombylius major).

Greater Bee Flies arrive in my area in April, when early-blooming flowers like Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) begin to open.

I’ve often observed Greater Bee Flies hovering over open ground on sunny spring days—they may have been females searching for the nest openings of their parasitic host, mining bees of the genus Andrena.

Worldwide Bee Fly Distribution

There are about 5000 species of bee flies worldwide and about 800 in North America north of Mexico. They’re most commonly found in arid regions where they are particularly valuable pollinators of flowering plants.

Nectar Thieves

Posted in Butterflies, Ecology, Native Plants, Nature, tagged Cardinal Flower, Lobelia cardinalis, nectar thieves, Papilio troilus, pollination, spicebush swallowtail on January 13, 2013| 6 Comments »

In my previous post, I wrote that the mutually beneficial relationship between Cardinal Flowers and their pollinating hummingbirds could be disrupted by an interloper.

The interloper in this case is the Spicebush Swallowtail butterfly (Papilio troilus). The Spicebush Swallowtail is considered a nectar thief, a term used by ecologists to describe an insect that enters a flower to obtain nectar but that doesn’t pollinate it because the insect is physically incompatible with the flower. When the Spicebush Swallowtail sips nectar from a Cardinal Flower, its body usually doesn’t contact the flower’s reproductive parts sufficiently to pick up or deposit pollen.

Spicebush Swallowtails, sometimes two or three at a time, often descend upon my backyard Cardinal Flower patch to feed on nectar. If a hummingbird notices, it usually chases the swallowtails away, but the swallowtails quickly return.

The Spicebush Swallowtail is the only species of butterfly that I’ve seen feeding on Cardinal Flowers. I wondered why, since other butterfly species, like the Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) and Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele), often visit my backyard. I learned that the Spicebush Swallowtail has the longest proboscis (over 9/10”, or 2.31 cm) of all the butterflies in my area and may be the only species that can reach the nectar at the base of the Cardinal Flower. The closely-related Tiger Swallowtail has a proboscis that’s about 2/3” (1.17 cm) long, while the Great Spangled Fritillary’s proboscis is just under 6/10” (1.45 cm) long. Neither of these two species has shown an interest in the Cardinal Flowers.

Cardinal Flowers and Hummingbirds–Pollination Perfection

Posted in Birds, Ecology, Native Plants, Nature, tagged adaptation, mutualism, plant reproduction, pollination, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, self-compatible on January 12, 2013| 9 Comments »

In mid to late summer, the brilliant red blooms of the Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis) brighten areas with moist to wet soils in eastern North America as well as farther west to the southwestern states and California. The Cardinal Flower is an ideal example of a plant that has flowers adapted for a single type of pollinator, the hummingbird. The only hummingbird species in northeastern North America is the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris). This hummingbird gets its name from the iridescent red patch on the throat of the males—females lack the red patch. I’ve enjoyed watching these tiny, energetic birds darting about in a patch of Cardinal Flowers in my backyard, sipping nectar while performing valuable pollination services.

The show starts in mid summer

Cardinal Flowers extend their spike-like inflorescences upward beginning in mid summer and ultimately reach a height of 24” to 48” (60 to 122 cm). Individual flowers open in succession from the bottom of the stem to the top over a period of about six weeks. Each spike can have several to over 50 individual flowers. Each flower consists of a tube about 1 1/2” (3.8 cm) long that flares out into five petals—two outstretched petals forming an upper lip and three downward pointing petals forming a lower lip.

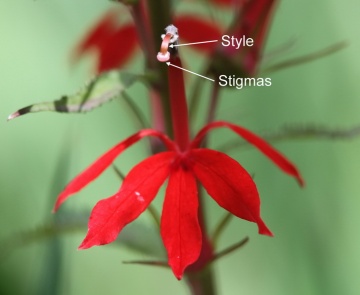

Projecting upward from between the two upper petals of the tubular flower is another tubular structure that contains both the male and female reproductive parts. When the flowers first open, they’re in the male phase. In this phase, pollen is held in the tip of the tubular reproductive structure. A tuft of white hairs, looking like a tiny beard, extends beyond the tip. When the tuft of hairs is pushed back, the tip of the tube opens and releases pollen.

After about five days, the flower shifts to the female phase. In this phase, the female structure called a style elongates and extends out beyond the end of the tube. On the tip of the style are the stigmas, which are receptive to pollen from male phase flowers. At any given time, a spike can have unopened flowers, male phase flowers, female phase flowers, and remnants of flowers that have finished blooming.

Hummingbirds at your service

Hummingbirds are attracted to red flowers, and the Cardinal Flower certainly meets this requirement. Hummingbirds also have long, grooved, forked tongues that can lick nectar from the bases of long, tubular flowers like Cardinal Flowers. The hummingbird feeds while hovering at the flower’s opening, beating its wings at about 55 times per second.

As the hummingbird hovers at the Cardinal Flower’s opening and enjoys a drink of sweet nectar, the top of its head comes in contact with the flower’s reproductive parts. If the flower is in the male phase, the hummingbird’s head will brush against the tuft of hairs at the end of the reproductive tube and receive a dusting of pollen.

If the flower is in the female phase, pollen already on the hummingbird’s head will stick to the female stigmas. Since male and female phase flowers are present at the same time, the hummingbird usually is successful in transferring pollen to female phase flowers. Cardinal Flower is self-compatible, so seeds will be produced whether the pollen is transferred to a female phase flower on the same plant or on a different plant.

But … beware an interloper

This mutually beneficial relationship between Cardinal Flowers and hummingbirds can be disrupted by an interloper. Learn more in the next Eye on Nature blog post.

Cicada Killers

Posted in Ecology, Insects, Nature, tagged cicadas, Crabronidae, digger wasps, larvae, predators, Sphecius speciosus, wasps on September 6, 2012| 2 Comments »

Occasionally, I’ve come across a cicada lying on the ground, motionless, but seemingly alive and wondered how it got that way. Earlier this summer, I found out.

In late July, I was standing on my patio when I spotted a wasp-like insect that was about 1 ½ to 2 inches (38 to 51 mm) long. Its body was brownish-black with yellow markings, and it had shiny, rust-orange wings and legs. It flew slowly back and forth just above the patio’s surface and then entered what appeared to be a freshly excavated hole between two patio stones.

I did a Google search on “large burrowing wasp”, and the first hit was a Wikipedia entry on Sphecius speciosus, a large digger wasp commonly known as the Eastern Cicada Killer. The description and photos matched the insect that I had seen.

Cicada Killers, true to their name, hunt and capture annual cicadas to feed their larvae. I usually start to hear the loud, raspy songs of male cicadas in early July. I learned that Cicada Killers emerge soon after. After mating, female Cicada Killers excavate burrows that will hold both their larvae and the cicadas that the larvae will feed on. They locate their burrows in well-drained soils, often in patios and sidewalks, and always near large deciduous trees where cicadas feed on sap.

Although the Cicada Killers are large and somewhat frightening looking, they actually are docile around people. The males don’t have stingers, and the females will deliver a mild sting only if handled roughly.

Excavating the burrow

The next day, I watched a female Cicada Killer excavate a new burrow beneath the patio. She entered a hole in the sandy soil between the patio stones and, after several minutes, backed out of the hole, pushing the soil with her spurred rear legs. She looked like a mini bulldozer working in reverse, and she amassed a quantity of excavated soil many times larger than herself. I read that Cicada Killer burrows can be up to three feet long and extend two feet below the surface. I also confirmed what I had read about their docility—I approached the female closely but she was oblivious to my presence.

The hunt for cicadas

When her burrow is complete, the female Cicada Killer begins hunting. She hunts by sight and, after capturing a cicada, she uses her stinger to inject it with venom that both paralyzes and preserves the cicada, but does not kill it. Keeping the cicada alive keeps it in a fresh, edible condition for longer than if it were dead. The Cicada Killer flies from the tree back to the burrow with her prey—no easy feat, since the cicada is about twice the weight of its killer. After the larvae hatch, they begin to feed upon the paralyzed, still living cicadas that their mother has provided.

Mishaps happen

Cicada Killers sometimes accidentally drop their heavy prey when flying to the burrow. Cicada Killers aren’t strong enough to take flight from ground level with a cicada in tow, so they often abandon it. They also may abandon their prey if they mistakenly land too far from their burrow entrance. The motionless cicadas that I’ve found were likely abandoned by Cicada Killers. Unfortunately for them, the paralyzed cicadas are easy prey for ants and birds.

Looking forward to next year’s show

During the several days that I saw the female Cicada Killer flying about the patio, I never witnessed her toting a captured cicada back to her burrow. Hopefully, she did so unseen, so that I can have a better chance of watching these fascinating insects again next year.

For more information

Professor Chuck Holliday of Lafayette College in Pennsylvania has an excellent website on the biology of Cicada Killer Wasps.

Giant Swallowtail Larvae

Posted in Ecology, Insects, Nature, tagged butterflies, Dictamnus albus, gas plant, larvae, larval host plants, Orange Dog, Papilio cresphontes on August 30, 2012| 2 Comments »

This, my third post about the Giant Swallowtail butterfly (Papilio cresphontes), will focus on the larvae.

The young larvae are a shiny dark brown with cream-colored patches–they look like warty bird droppings. As they get older, the larvae develop scale-like markings about their heads and look like tiny snakes when viewed from the front. These disguises help to protect the larvae from predators—young larvae appear unpalatable and older ones resemble frightening adversaries. The larvae also can ward off potential predators by thrusting out their osmeterium, a pair of bright red, retractable horn-like structures. In older larvae, the osmeterium emits an unpleasant stench that repels potential invertebrate predators like spiders and ants. The osmeterium’s likeness to a snake’s tongue may frighten larger predators like birds. The Dragonfly Woman has a nice video on her blog of a larva extending its osmeterium.

After molting through five stages, the larvae ultimately reach a stout 2 to 2 1/2” (51 to 64 mm) long. They then seek out a nearby vertical stem or other surface on which to pupate. In northeastern North America, the Giant Swallowtail overwinters as a pupa.

In Florida’s warm climate, where Giant Swallowtail butterflies are common, there are two or three generations each year. There, the larvae often feed on citrus trees like sweet orange and are called Orange Dogs. They’re considered pests because they can defoliate young trees.

Update on the larvae in my garden

In my August 19 post, I wrote that I had found three Giant Swallowtail eggs on the Gas Plant (Dictamnus albus) in my garden, followed by two larvae about a week later. As of today, I’ve counted six larvae scattered on the leaves of the Gas Plant. Five larvae are about the same size—5/8” (16 mm) long. The sixth larva, which I discovered yesterday, is smaller, only about 1/4” (6 mm) long. I suspect that the small larva may be the offspring of an adult female that visited my garden unseen several days to a week after the adult I saw on August 3.

The larvae often sit on the tops of the Gas Plant leaves, clearly visible bird-dropping imitators. Occasionally, one will appear restless, and will travel back and forth over the leaves for several minutes before settling down again. I’ve read that they feed mostly at night, but I occasionally have seen a larva munching on the Gas Plant leaves during the day. If I touch them with a twig, they arch their backs and thrust out their bright red osmeterium.

I’ll continue to monitor the larvae on my Gas Plant and hope to post occasional updates on their development.

Giant Swallowtails moving north

I first thought the Giant Swallowtail butterfly that visited my garden on August 3 was a rare sight. Since then, I’ve learned that lots of people in my area and farther north have seen Giant Swallowtails this year and that sightings in the north have been increasing for about five years. This northward movement may be due to changing weather patterns, decreased pesticide spraying, or some other as yet unknown reason. Whatever the reason, we northerners have had the treat of seeing these large, beautiful butterflies close to home.

Giant Swallowtails Head North Again

Posted in Butterflies, Ecology, Insects, Nature, tagged lepidoptera, nature books, pesticides, population fluctuations, rare species on August 17, 2012| 16 Comments »

It’s always exciting to see a new species of plant or animal, especially one that’s considered rare in your area. This happened to me earlier this month, when a Giant Swallowtail butterfly (Papilio cresphontes) visited my northern New Jersey backyard. This large, attractive butterfly is common in Florida, but becomes less abundant farther north.